I went to see Cuts in the Day, the first major exhibition in the UK by Dani and Sheilah ReStack, when it opened. I hadn’t been London since 2019 when I saw the pop singer Robyn. As with most people there have been large shifts in my life since that time, and a renewed reflection on what it means for my body to be in space in proximity to other bodies.

The exhibition responds to the accompanying show of work by queer artist, recluse and fisherman Forrest Bess (1911-1977). They share concerns around gender and sexuality, how bodies are made and reproduced, and relationship to the rural.

I subsequently met Dani, Sheilah and their dog Findley on zoom to talk about bodies, transformation and kinship.

*

Mathew: Can you talk a bit about Cuts in the Day and the relationship to Forrest Bess’ work?

Sheilah: Cuts in the Day is something we came up with in relation to Forrest Bess, in the sense of cutting and coming across a whole diagrammatic of various symbols for all kinds of things in Bess’ work. In his list of symbols were triangular shapes for various types of cuts that correlated in some manner to his own experience of self-cutting.

But we also thought about it in relation to film making, and cutting, and also in relation to the shape of a day. This idea [that within] the mundane quality of a day there is the capacity to take cuts which transform it into something else someway: making a portal quality or portal potential of a day.

Dani: Bess being a seeker—a searching seeker—really resonates in our art. I would say we’re not looking for the transcendental as much as we are looking for transformation. So we made this underwater shot in relation to him. It was a method of communication as water is fluid and moves through space. Ideally we would have gone to his fishing location in Chinquapin Bayou, near Bay City, but here we are in Ohio so we sought out various bodies of water here—but it’s very polluted so the quality of the image was just too murky.

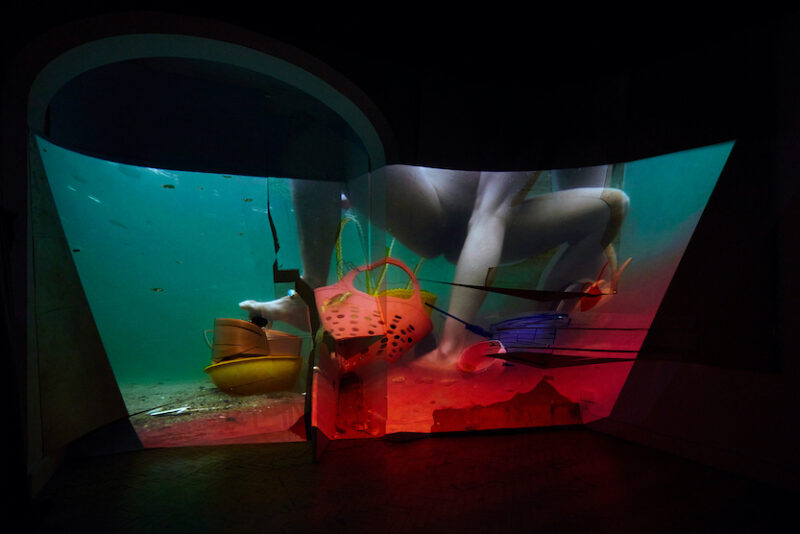

So we went to the Lake Michigan which really was clearer, but there were waves and all the props underwater were moving and we needed them to be still so we could map the image onto shapes. We wound up in Nova Scotia, where Sheilah is from, and found the water clear and still, and it worked. That shot was projected into a corner of the gallery—we built out shapes to receive the image and then flipped from image to white—just the white light—to reveal the screen structure. Last night I was looking through a bonfire and the waves that occur when you look through heat—it’s always in flux. So this little cliché ‘things aren’t always as they seem’, for me is very true, and it’s true about relationships and people of course.

Sheilah: It’s interesting as I’m listening to Dani, I feel like the ultimate goal would have been to go back to Chinquapin or Bay City. Forrest Bess was in this rural location and isolated. In a way, we share this isolation to some degree being in Ohio, and certainly where I grew up in Nova Scotia. I don’t know if you can get much more isolated than where I grew up you know? So I feel like there is something like communication, and it was interesting to me there are three places used or referenced—if you draw a line [between them] it forms a triangle too.

‘Blood and Water for FCB’, like Dani was saying, is some method of communication, or transmission, or contamination. One drop of blood in the water; where does that end up going ultimately? But it was also in relation to, the first time, when [Forrest Bess] cut himself, he talked about it as this ecstatic moment. Blood and urine was released, or blood and water, and [he] compared it to a religious experience. We were thinking about trying to recreate those elements of transformation, maybe give those things, the water and the blood, back into the world and see what would happen this time around.

Dani: I’m squatting and Sheilah is the tripod holding me up. The idea of birth in that position, midwives encourage that position. So I felt it was a birth of the pots and pans. [Then with] the voiceover of Monique Wittig’s ‘Les Guérillères’ that she calls out in her book, the birthing of Guérillères, the birthing of possibilities. Blood, you can explain this better, because blood for women is pretty predictable, it’s regular…

Sheilah: For a while it is predictable, until you hit menopause, which nobody ever talks about—as they don’t talk about bleeding really, either. I actually feel it (the blood) is really formal. It obscures the whole canvas, in a way that is seductive. Also I feel like blood in terms of who gets to use it, it tends to get gendered in our society, so I’m trying to pull back on who is allowed to use it as subject or material.

Mathew: Also with blood, the tonal resonance it makes shifts with that gendering. Particularly in the context of film and video history, when it’s used by men, it’s often quite horrifically violent or grossly humorous. One of the elements of your work I’ve always been interested in is how it sits between being incredibly intimate and complex, but then also very funny. Maybe blood is one of those things that is simultaneously repulsive and alluring. There is a push pull?

Dani: Blood is fun, definitely fun. This one was made with molasses and food colouring. There was this little hope that a fish would come and want to eat it.

Mathew: I’ve been thinking a lot about scale and poetry in relation to Cuts in the Day.

Scale in the collaborative video installation and in the individual works—drawings and sculptural photographic works—there is a play of scale in both, as well as in Forrest Bess’ work where scale and constraint seem important.

Poetry in terms of the collaborative video installation, is it more a poem than a story? This relates to an anecdote poet Sophie Collins shares in ‘Small White Monkeys’ when a friend is asked for their definition of a witch and they say ‘someone who uses language to make tangible changes in the material world’. I was thinking of that in relation to how the works use their form as art, and of using language to make transformative change in your world. I don’t know if that’s something you think it is doing, or trying to do?

Dani: Sheilah and I feel differently when someone describes the work as poetic.

Sheilah: I have always been afraid that things that are poetic become pretty, or less difficult in a way. There are all kind of ways the word poetry can be used, and I feel that’s one of the ways it can be used.

Dani: But poetry can be so challenging.

Sheilah: You were talking about this transformative capacity and I think we are always searching for that, individually and collaboratively, through what we have available.

With the video installation I’m thinking about that idea of transformation, and the calling out of names. When you repeat a name sense is dissolved out of it. Maybe that’s what happens with the piece itself, it goes red and then you start over again. It goes red and then you start over again.

For a long time, this was several years ago now, we kept on talking about the difference between a loop and a single channel. What is it? How do you activate that? I don’t really have an answer to that per se, but this piece lives in that world of some type of looping chant, or maybe it’s like a spell, you keep saying this spell and hope that something happens.

Mathew: In the Feral Domestic trilogy and Cuts in the Day, there seem to be themes of violence and repair. Within the loop, the full red and the full white screens are quite violent cuts and then it gets repaired as the loop comes back around. I was also thinking about the moment where you are stitching into the image of a glacier on a sewing machine over and over in ‘Future From Inside’. Do violence and repair figure in the work?

Sheilah: Cuts in the Day, when I first talked about it, was the capacity for it to be transformational, but there are also the cuts in the day that make you want to cry. Being ‘in relation’, whether in a relationship or living in this world, there are just so many instances of hurt—personal, global, whatever. I’m not saying there is any reparative thing that will fix it, there’s just the desire to keep trying. I’m thinking about Dani’s painting, the fur is stapled to the wood—there is something violent about that act, but at the same time it’s also in the pursuit of the construction of something else.

Dani: A suture of sorts. You get staples in surgery: it’s about commitment, As I’m very familiar with getting cut and leaving, this kind of repair is in order to stay. I think that repair is also forgiveness.

This is a side note but I don’t have as much control over the stapler as I would like, but they are supposed to be little crosses and that’s a forgiveness symbol to me. I know it means a ton of negativity for a lot of people, but the cross is a forgiveness piece.

Mathew: There has been a resurgence in discussion around family abolition from a leftist feminist perspective. A lot of that conversation is about not wanting to privatise the act of caring. I was wondering about your thoughts on this with there being so much kinship in your work, as well as the public showing of so much beautiful intimacy, and how you work through how explicit to make intimacy.

Dani: We are a foster family to a little girl and are learning about kin in a whole new way.

But you know, I feel kinship with animals and want to nurture that. Usually the animal has to be dead to have close enough contact. The kinship is really a sense of honour and fascination. Look at these tiny eyelashes on this possum, how gorgeous, I would never be able to know that watching a possum run through the yard. Could there be a kinship of honour? Homage? I mean there is a kinship for us between Prince and Chantal Akerman—can that be called that as they give so much by being who they are. I think of how that word [kin] can expand, but I don’t know about these words ‘abolition of family’.

Sheilah: When Dani is talking about our relationship as a foster family, you get pushed and pulled from a purity of love or care, and then the way gets all fucked up when you start to place that into the heteropatriarchal systemic racist societal structure. I just feel like I wish for there to be clarity of relation or how to make a family in a way that could be truly radical, but everything feels like it somehow ends up being compromised or sullied by just our exitance in this wider context.

I like to think the work we make together, or individually, makes possibilities for other queers or women. I like to think that, but also, it’s probably instrumentalised so that an institution can say it had its queer show. I’ve seen so much queer culture get ingested and puked out as something palatable and I don’t want that. But at the same time I’m compelled to make things that could ultimately become ingested and puked out as something that is palatable.

So I don’t know, I guess what I am trying to say is I feel both this purity of desire and this simultaneous inescapability of the systems that hold us. I think that our experience with fostering in particular has made that so front and centre. One thing that feels like a way out is friends. I think [of] that moment in ‘Future From Inside’ of inviting people to be in the studio and put the glacier water in their eyes. I think I’m talking about how to get past this feeling of just being thwarted, to move from this private space of home into the world in a way where I sometimes feel like I can’t make a move? Only through friendship.

*

‘Dani and Sheilah ReStack have embarked on an artistic relationship that is formally and emotionally adjacent to their domestic lives, a quotidian zone they share with their daughter Rose. Both artists have established careers on their own. Neither Dani’s video work nor Sheilah’s multimedia performance and installation work could exactly prepare us for the force of the women’s collaborative efforts.’ Michael Sicinski, Cinema Scope, 2017

ReStack collaborations have shown at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, Iceberg Projects Chicago, Toronto International Film Festival, Images Film Festival, Toronto, Lyric Theater, Carrizozo, NM, The New York Film Festival CURRENTS, Leslie Lohman Project Space, Gaa Wellfleet and The Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio. They have received grants from the Canada Council for the Arts, and the Hanley Award. They have been residents at The Headlands and the MacDowell Colony.

Forrest Bess was born in 1911 in Bay City, TX, and died there in 1977. He studied architecture at college before joining the war effort as a member of the camouflage unit. A fixture in the early artistic communities of Houston and San Antonio, he painted his first mature visions in 1946, having sublimated his visionary ‘source’ the previous decade. He began showing at Betty Parsons Gallery four years later. His works were well known by many of the leading curators of his day, and were acquired by influential collectors; yet Bess died in relative obscurity. Often described as an ‘artist’s artist’, he has been the subject of renewed curatorial and scholarly attentions in recent years.