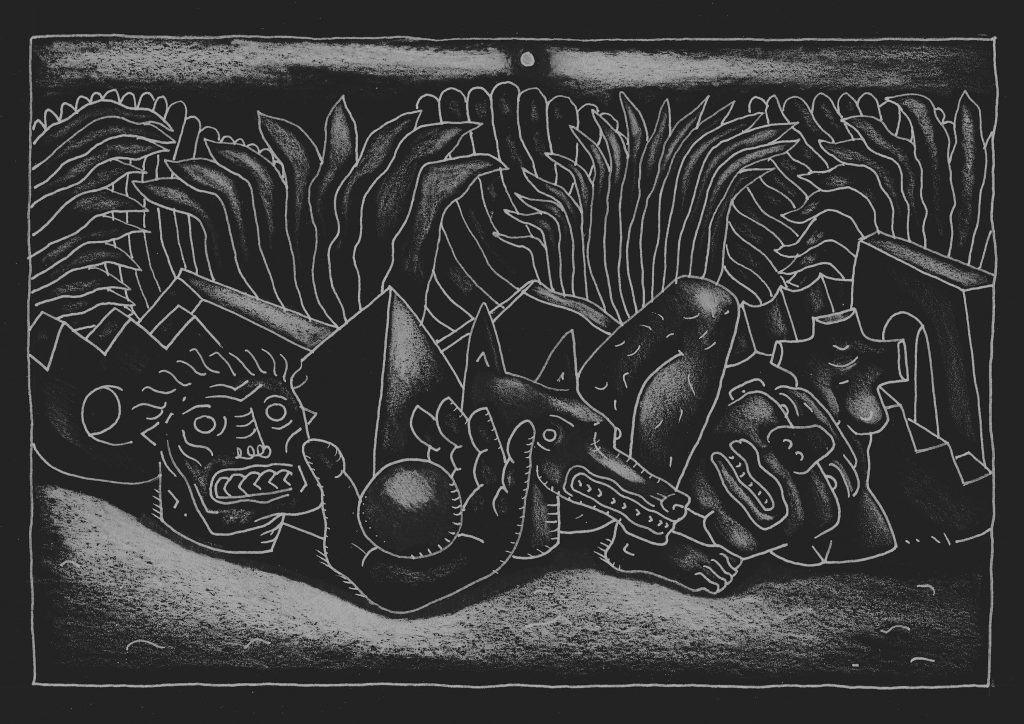

Text commissioned by Kendall Koppe gallery to accompany Miguel Cárdenas’s exhibition Mystic Animals and the Juggling of Hot Stones.

‘reaching out for him – wildebeests, pigs,

the oryxes with their black matching horns,

javelinas, jaguars, pumas, raptors. The ocelots

with their mathematical faces. So many kinds of goat.

So many kinds of creatures.’ (1)

EXTERIOR: A large red brick rectangle scowling in the landscape. Vertical lines and slits running up and down the walls. Plumes of rectangular brutality. A church in East Kilbride, the carpark of which is being used as a court. His Dishonour from Sterling Karat Gold (2) is overseeing the trial on his half throne half toilet.

Animals have been put on legal trials throughout human history. This has been less to consider the motivations and guilt of an animal, but more that they enacted violence. This seemed particularly common in France, in the 14th Century a pig was hanged in Normandy after being put on trial for infanticide (3). Pigs were common culprits but a whole range of animals were tried including ‘caterpillars, flies, locusts, leeches, snails, slugs, worms, weevils, rats, mice, moles, turtle doves, pigs, bulls, cows, cocks, dogs, asses, mules, mares and goats’. Their deaths were considered to be a deterrent to other beasties. Occasionally the animal’s were acquitted, but this isn’t a reading of the animals understanding of its actions, but more often they are carrying out the divine will of a god.

‘Take your sharp knife and insert into the anus. This is found near the tail on the belly. From here, cut along the belly towards the head all the way to the base of the gills. Spread the abdominal cavity open and pull out the guts with your fingers or a silver spoon. Use your knife to carefully cut any bits that are still attached. You may need to get your whole hand in there.’ (4)

I’m paraphrasing a screengrab of a tweet I showed you months ago and it has long since disappeared, so I apologise for not being able to reference and credit, but it is something along the lines of my cat teaches me about non-verbal consent and I teach them how to shit in a box. When you come in from work and go to the toilet my cat comes to the litter tray next to you to squat and expel in union. Obviously a domestic cat, not a jaguar.

‘Colonialism implemented this process on a genocidal level. Indeed, the relationship between racialisation and gendering is often underplayed. People who did not understand their bodies in a binaried fashion were subject to devastation from colonising forces.’ (5)

INTERIOR: swathes of suffocating surface coagulating around, I can’t work out where anything starts or ends, a murky colour I can’t define, am I inside a sack or a stomach. I’m wearing a blue Adidas tracksuit with the classic three white stripes down the arms and legs.

I am uncertain of how objects experience time – or if they experience time. But I am uncertain of how I experience time or how much I try to make it into a pattern I can understand. Through primitive accumulation the way of experiencing time was violently enforced, and with this a way that we understand narrative structure. To an extent this impacted who or what and how a story was told, once the dominance of authoritative human voice and linear narrative was displaced you untruthfully said it was a new development.

As a child I was very worried about objects feeling neglected or jealous. Very presumptuous of me to assume they would have feelings akin to mine. I would make sure to use my objects in equal measures to make sure they wouldn’t take revenge on me. This fear extended to hands, meaning I would try to do things with both my hands so they each felt loved – out of fear that one hand would revolt and attack me.

What I want to say about The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (6) is not just non-linear or violent forms of time and narrative, but the importance of us developing our own connective tissue. I read a headline recently ‘Boozy feral pig steals beer, gets drunk and starts fight with a cow’. I then tried to read about animal self-medication, but it mainly spoke about them eating grass and furry leaves to clear out their intestines.

‘Relation exists in being realized, that is, in being completed in common place’ (7)

EXTERIOR: I am standing in an oppressive canopy. The inside of a green, brown, yellow, pink bag. It isn’t temperature or air that is oppressive, although they are, but the overabundance of-surface. Everything here is competing for the same resource, the same light, myself included. I see a beak the colour of a nose, a hand which may be mine, a long furry protuberance from a voluptuous bud. I tread carefully although the damage is done. I am dressed as a sailor from Querelle De Brest (8), you are in shorts and a straw hat. You have the stern face of a grave (rectum).

In a documentary from 2008 (9) Louise Bourgeois describes a childhood experience of the posturing father at the head of the dinner table performing a party piece. “You have to understand that in a tangerine there are two important points” and cutting between these points her father peels a human figure. The joke is aimed at Louise (who was named after her heir seeking father Louis) as he considers the figure to be his daughter, paradoxically it can’t be as some of the connective tissue of the tangerine stands erect as a phallus.

The first thing I remember making is a sculpture (which is a grandiose way of describing it) of a lamb as a child at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Made from cardboard and loo rolls and cotton wool. I love lambs, and I still draw them frequently. This lamb has taken on a great figure in my mind, and the photograph I half recall of me holding it after making it.

As well as animals being tried for their roles in crimes, objects were also sometimes brought in front of the court (10). Athenian law required objects involved in murder to be cast outside the Athenian boundaries. In 1591 a Russian bell was banished for its role in the assassination of a prince. I am unsure what defence arguments these object’s had.

‘Insofar as we inherit that which is near enough to be available at home, we also inherit orientations, that is, we inherit the nearness of certain objects more than others, which means we inherit ways of inhabiting and extending into space.’ (11)

INTERIOR: A flat living room which may or may not be a squat. The walls are stripped and the plaster is stained green with age. The furniture is mainly mid century northern european with some rocks and boulders strewn around. There is a vase with a single dull pink anthurium spray. My teeth are grinding and gnashing before separating into a toothy grin.

A dog guides us through the underworld and we guide it to a representation of itself. Dogs are domestically intimate but hold the ability to harm as well as protect. My body is covered in a soft layer of hair, which is more sparse and long, rather than furry. The black dog in front of me appears hairless but is actually covered with a layer of downy fur. The dog I imagine is red and smooth wearing a mask of a human face.

The dog’s I grew up with were soft and begged for food. My mum’s dog brings me a stick for throwing that looks like a bird and I consider the benefits of microdosing on hallucinogens. All the way down.

Some Law academics have long been campaigning for human rights to be extended to non-human apes (12). Some parts of the world have recognised the personhood of great apes, although it is far from universal. At many points in history communities of humans have been seen as objects rather than people, and assigned the rights of a ‘thing’. These struggles for humans to be recognised as more than objects remain ongoing, and never feels fully secured. In this fight it is important to consider non-human sentience and its need for recognition that moves further than ‘thing’ with experiences beyond our conception.

The compositions of Cardenas’ paintings feel familiar but like they are obfuscating meaning from me. I want to read them as part of an art historical lineage of western art. When I think of masks I place them in relation to western discovery and appropriation, or I don’t talk about it which again reasserts this dominance. It’s not just that these modes and symbols were reappropriated into western art, but that my attempts to read them as narrative and commentary, rather than feelings and autonomous beings in a bag-stage-painting misses something, and continues to deny the presence of indigenous thought. I need to roll my tongue and tense my jaw and allow the development of connective tissue.

‘and not alone the lips … the cheeks … the jaws … the whole face … all those- … what ? .. the tongue? .. yes … the tongue in the mouth … all those contortions without which … no speech possible … and yet in the ordinary way … not felt at all … so intent one is … on what one is saying … the whole being … hanging on its words’ (13)

Mathew Wayne Parkin 2022

- Postcolonial Love Poem, Natalie Diaz, 2020

- Sterling Karat Gold, Isabel Waidner, 2021

- The Pig Walked Free, Michael Grayshott, 2013, LRB December 2013

- How to Gut a Fish in the Wild, https://coolofthewild.com/how-to-gut-a-fish/

- Making and Getting Made: Towards a Cyborg Transfeminism, Sølvi Goard, 2017, https://salvage.zone/making-and-getting-made-towards-a-cyborg-transfeminism/

- The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula K. Le Guin, 1986 https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/ursula-k-le-guin-the-carrier-bag-theory-of-fiction

- Poetics of Relation, Edouard Glissant, translated by Betsy Wing, 1997

- Querelle De Brest, Jean Genet, 1974

- Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress, and the Tangerine, Dir. Amei Wallach, 2008

- The Pig Walked Free, Michael Grayshott, 2013, LRB December 2013

- Queer Phenomenology, Sara Ahmed, 2006

- The Great Ape Project: A First Step Toward International Recognition Of The Rights Of Nature?, Daniel Cheater, 2019, https://allard.ubc.ca/about-us/blog/2019/great-ape-project-first-step-toward-international-recognition-rights-n ature

- Not I, Samuel Beckett, 1973